Barbiturates drug profile

Barbiturates drug profile

Barbiturates are synthetic substances manufactured as pharmaceutical products. They act as depressants of the central nervous system. The parent compound barbituric acid was first synthesised in 1864 but the first pharmacologically active agent, barbital, was not produced until 1881 and introduced to medicine in 1904. The most widely used compound, phenobarbital, was synthesised in 1911 and first used clinically the following year. While some 2 500 derivatives have been synthesised, only about 50 have ever been used medically.

The use of barbiturates as sedative/hypnotics has largely been superseded by the benzodiazepine group. Some barbiturates are now more widely used in the treatment of epilepsy and shorter acting molecules are used in anaesthesia. Twelve barbiturates are under international control.

Chemistry

The pharmacologically active barbiturates are based on barbituric acid (CAS 67-52-7), the fully systematic (IUPAC) name for which is 2,4,6-(1H,3H,5H)-pyrimidinetrione. The different drugs have various substituents on this basic skeleton, usually at the 5 position.

Molecular structure: barbituric acid

Phenobarbital, also known as phenobarbitone (CAS 50-06-6), is the most widely used barbiturate. The IUPAC systematic name is 5-ethyl-5-phenyl-2,4,6(1H,3H,5H)-pyrimidinetrione. It is also referred to as 5-ethyl-5-phenylbarbituric acid.

Phenobarbital

Molecular formula: C12H12N2O3

Molecular weight: 232.2 g/mol

Physical form

Tablets, capsules, injectables, elixir, suppositories.

Pharmacology

Barbiturates are a group of central nervous system depressants which produce effects ranging from mild sedation to general anaesthesia. Depending on how quickly they act and how long their effects last, they can be classified as ultra-short-, short-, intermediate-, and long-acting. Compounds with a 5-phenyl substituent, e.g. phenobarbital, have selective anti-convulsant activity which makes them useful in epilepsy. Barbiturates act by enhancing the action of GABA through binding to a site on the GABAA receptor/chloride channel, a property they share with benzodiazepines; however, the binding sites of the two drug types differ and as a result, the action of barbiturates is less specific. Because of this, the therapeutic index is low. The resulting risk of overdose means that their use as sedative/hypnotic agents is no longer recommended.

Adverse reactions include drowsiness, sedation, incoordination followed by respiratory depression, headache, gastrointestinal disturbances, confusion and memory impairment. Users may appear to be inebriated because they experience paradoxical excitement or euphoriant effects that are comparable to those of morphine. Some individuals are reported to have consumed between 1.5 and 2.5 g per day in order to maintain a state of intoxication resembling that caused by alcohol. A residual central nervous system depression may occur the day following a hypnotic dose. This may involve impairment of judgement and fine motor skills (e.g. driving, operating machinery, etc) for up to 22 hours.

Accidental deaths and suicide attempts involving barbiturate use have been reported. A study of fatal overdoses due to anxiolytics and sedatives in the UK between 1983 and 1999 reported a figure of 146.2 fatal toxicities per million barbiturate prescriptions compared to just 7.4 per million for benzodiazepines. The lethal dose varies from 2–3 g for amobarbital and pentobarbital to 6–10 g for phenobarbital. Lethal overdoses are associated with plasma levels of 60 mg/L of phenobarbital but only 10 mg/L of short-acting compounds such as amobarbital and pentobarbital. The concentrations that can cause death are lower if alcohol or other central nervous system depressants such as benzodiazepines are present. Symptoms of an overdose include incoordination, slurred speech, difficulty in thinking, coma, respiratory and cardiovascular depression with hypotension and shock leading to renal failure and death.

Regular use of even therapeutic doses of barbiturates is very likely to result in the development of tolerance and dependence. While tolerance to the sedative and intoxicating effects develops, the lethal dose is not similarly increased. As a result, acute barbiturate poisoning may occur at any time during chronic intoxication. Abrupt withdrawal from barbiturates can be life-threatening, unlike withdrawal from opiates. Symptoms of withdrawal are similar to those of alcohol withdrawal. The individual becomes restless, anxious, apprehensive and weak, complaining of abdominal cramps, nausea and vomiting. The symptoms reach their peak during the second and third day, when convulsions may appear. Up to 75 % of subjects may have one or multiple seizures and about 66 % may develop a delirium lasting several days. The delirium resembles that sometimes seen during alcohol withdrawal (delirium tremens) and involves anxiety, disorientation and visual hallucinations. During the delirium, agitation and hyperthermia can lead to exhaustion, cardiovascular collapse and death. But this is not inevitable and the symptoms can disappear with time (typically after eight days or so).

Table 1: Barbiturates under international control

| Name | Chemical name | Chemical formula | CAS No | Control status 1971 UN Convention Schedule | Medical use | Pharmaceutical name |

| Allobarbital | 5,5-diallylbarbituric acid | C10H12N2O3 | 52-43-7 | IV | insomnia | Dialog® |

| Amobarbital | 5-ethyl-5-isopentylbarbituric acid | C11H18N2O3 | 57-43-2 | III | insomnia, sedation, seizures | Amytal ® Tuinal ® |

| Barbital | 5,5-diethylbarbituric acid | C8H12N2O3 | 57-44-3 | IV | insomnia | Malonal Veronal |

| Butalbital | 5-allyl-5-isobutylbarbituric acid | C11H16N2O3 | 77-26-9 | III | Lanorinal | |

| Butobarbital | 5-butyl-5-ethylbarbituric acid | C10H16N2O3 | 77-28-1 | IV | insomnia, sedation | Soneryl® |

| Cyclobarbital | 5-(1-cyclohexen-1-yl)-5-ethylbarbituric acid | C12H16N2O3 | 52-31-3 | III | Cyclodorm® | |

| Methylphenobarbital | 5-ethyl-1-methyl-5-phenylbarbituric acid | C13H14N2O3 | 115-38-8 | IV | epilepsy, daytime sedation | Prominal® |

| Pentobarbital | 5-ethyl-5-(1-methylbutyl)barbituric acid | C11H18N2O3 | 76-74-4 | III | insomnia, sedation, seizures | Nembutal® |

| Phenobarbital | 5-ethyl-5-phenylbarbituric acid | C12H12N2O3 | 50-06-6 | IV | epilepsy | Luminal® Gardenal® |

| Secbutabarbital | 5-sec-butyl-5-ethylbarbituric acid | C10H16N2O3 | 125-40-6 | IV | Butabarb® | |

| Secobarbital | 5-allyl-5-(1-methylbutyl)barbituric acid | C12H18N2O3 | 76-75-3 | II | insomnia, sedation, seizures | Quinalbarbitone Seconal® Tuinal® |

| Vinylbital | 5-(1-methylbutyl)-5-vinylbarbituric acid | C11H16N2O3 | 2430-49-1 | IV | Optanox® |

Synthesis

The synthesis of barbiturates is mostly performed by the pharmaceutical and chemical industry, but descriptions of their synthesis from appropriate malonyl esters and urea appear on the Internet.

Mode of use

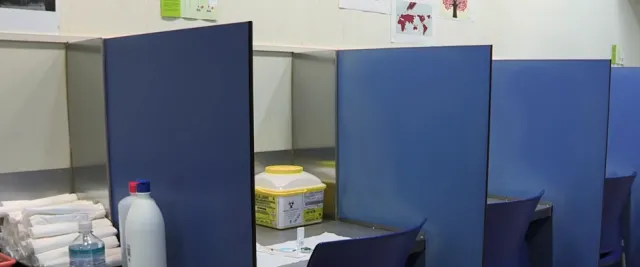

Barbiturates are usually swallowed as tablets but can be injected for both medical and non-medical purposes.

Other names

Numerous synonyms and proprietary names exist for the various barbiturates. User names include barbs, downers, Christmas trees, blue heavens, blues, goof balls, blockbusters, pinks, rainbows, reds, red devils, reds and blues, sekkies, sleepers, yellow jackets, etc.

Analysis

Barbiturates give violet colours with a mixture of ethanolic cobalt nitrate and pyrrolidine (Koppanyi-Zwikker test). The mass spectrum for phenobarbital shows a major ion at m/z=204 and others at 117, 146, 161, 77 and 103. The major ions for amobarbital (molecular weight 226.3) are at 156, 141, 157, 41 and 55, while those for thiopental (molecular weight 242.3) are at 172, 157, 173, 43 and 41.

Using gas chromatography-mass spectrometry, the limit of detection for phenobarbital in urine or plasma is 100μ g/L. Typical therapeutic concentrations are 2–30 mg/L while toxic effects have been reported with blood concentrations of 4–90 mg/L and fatalities with concentrations of 4–120 mg/L.

Control status

Twelve barbiturates are subject to international control through the 1971 UN Convention on Psychotropic Substances (see Table 1). Secobarbital was transferred from Schedule III to Schedule II in 1988 because of diversion from licit manufacture into the illicit trade. Amobarbital, cyclobarbital and pentobarbital were included in Schedule III in 1971, with butalbital added in 1987. The remaining compounds are in Schedule IV. Thiopental (CAS 76-75-5) is not subject to international control.

Availability of pharmaceutical barbiturates

The International Narcotics Control Board (INCB) reported that in 2007, total global licit production of barbiturates amounted to at least 543 metric tons, 447 tons of which was phenobarbital. Just five of the 12 barbiturates under international control accounted for 98.7 % of reported production between 2003 and 2007. Phenobarbital accounted for 78 % of production, followed by butalbital (8.6 %), pentobarbital (6.9 %), barbital (3 %) and amobarbital (2.6 %). China (50 %), India (11 %), the Russian Federation (10 %), USA (8 %), Denmark (7 %) and Hungary (7 %) were the leading manufacturers.

Medical uses

The original use of barbiturates as sedative/hypnotics is no longer recommended because of their adverse reactions and risk of dependence. Ultra-short-acting compounds such as thiopental, which is an analogue of pentobarbital where the oxygen at position 2 is replaced by sulphur (CAS 76-75-5), and methohexital (CAS 151-83-7) are used for anaesthesia, while long-acting derivatives such as phenobarbital are used in the treatment of epilepsy and other types of convulsions. Phenobarbital may be used in the treatment of withdrawal symptoms in neonates of mothers suffering from multiple substance dependence during pregnancy. It is the substance of choice for the treatment of neonatal abstinence syndrome in cases of combined dependence or benzodiazepine dependence. In veterinary medicine, pentobarbital is used as an anaesthetic and in euthanasia. Barbiturates are also reportedly used in lethal injections for executions in the US, for physician-assisted suicide and euthanasia and as a so-called ‘truth serum’ (thiopental).

Bibliography

American Academy of Pediatrics on Drugs (1998), ‘Neonatal drug withdrawal’, Pediatrics 101, pp. 1079–1088.

Brunton, L. L., Lazo, J. S. and Parker, K. L. (eds) (2006), Goodman and Gilman’s: The pharmacological basis of therapeutics, 11th edition, McGraw-Hill, New York.

Buckley, N. A. and McManus, P. R. (2004), ‘Changes in fatalities due to overdose of anxiolytic and sedative drugs in the UK (1983–1999)’, Drug Safety 27, pp. 135–141.

International Narcotics Control Board (2008), Psychotropic substances: Statistics for 2007 — assessments of annual medical and scientific requirements for substances in Schedules II, III and IV of the Convention on Psychotropic Substances of 1971, United Nations, New York.

King, L. A.and McDermott, S. (2004), ‘Drugs of abuse’ in Moffat, A. C., Osselton, M. D. and Widdop, B. (eds), Clarke’s Analysis of Drugs and Poisons, 3rd edition, Vol. 1, Pharmaceutical Press, London, pp. 37–52.

Lopez-Munoz, F., Ucha-Udabe, R. and Alamo, C. (2005), ‘The history of barbiturates a century after their clinical introduction’, Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment 1 (4), pp. 329–343.

Moffat, A. C., Osselton, M. D. and Widdop, B. (eds) (2004), Clarke’s analysis of drugs and poisons, 3rd edition, Vol. 2, Pharmaceutical Press, London.

Osborn, D. A., Jeffrey, H. E. and Cole, M. J. (2005), Sedatives for opiate withdrawal in newborn infants (Review), Cochrane Library Issue 3, Article No CD002053.

Sellers, E. M. (1988), ‘Alcohol, barbiturate and benzodiazepine withdrawal syndromes: clinical management’, Canadian Medical Association Journal 139, pp. 113–118.

Sweetman, S. C. (ed.) (2007), Martindale: the complete drug reference, 35th edition, Pharmaceutical Press, London.

United Nations (1989), Recommended methods for testing barbiturates under international control: manual for use by national narcotics laboratories, United Nations, New York.

United Nations (1997), Recommended methods for the detection and assay of barbiturates and benzodiazepines in biological specimens: manual for use by national laboratories, United Nations, New York.

United Nations (2006), Multilingual dictionary of narcotic drugs and psychotropic substances under international control, United Nations, New York.

Wolff, M. H. (ed.) (1859), The barbiturate withdrawal syndrome, Munksgaard, Copenhagen.